Back home in Freistatt 1944-1945

This local article in the Monett Times from November 10,1944 describes how dedicated the German Community of Freistatt was to the war effort. The banner in the photo shows a banner of blue stars surrounded with a red border and gold fringe. Under each star, the name of a local boy who was serving in the war is embroidered. The article states that "Thus far, no gold stars needed to replace a blue one."

Not only did Freistatt send 53 of their young men to war, the folks at home did all they could as well. An excerpt from this article states: "Every War Bond Drive that has been put on, in this community has always gone over the quota set for this district. The Walther League has appointed a special Army and Navy Secretary. Her duty is to keep all new addresses and address changes posted on the bulletin board in the corridor of the school. The church's bulletins, the League's paper "The Give and Take" and other material are mailed regularly to the boys by this Secretary. Individual Leaguers write letters regularly to every boy away in service. The War Chest Drive workers are always drawn from the Walther League Members. The citizens give liberally to this War Chest because they know that the money will be used for worthy causes, not only in this country, but also in the war torn and stricken lands over there."

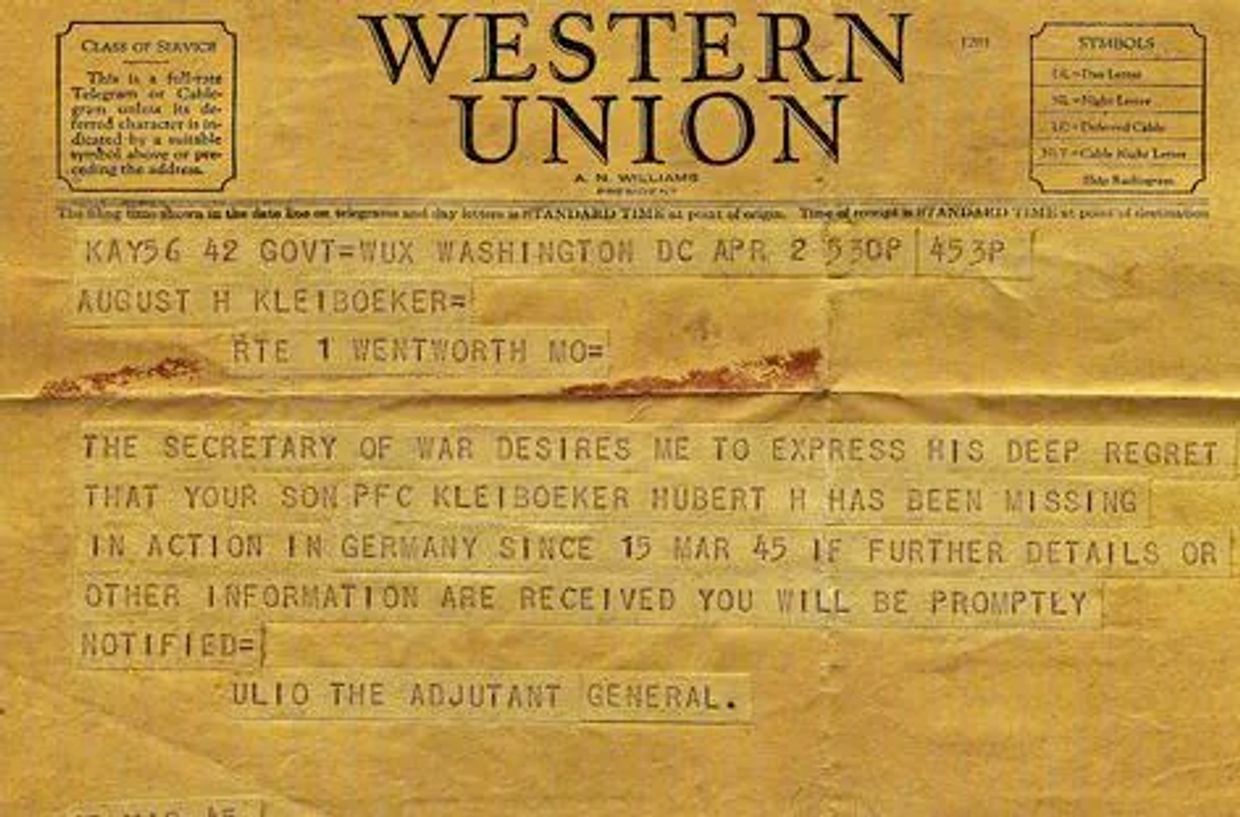

April 2, 1945: Kleiboeker Family receives MIA Telegram

Even more letters were written after that Telegram of April 2nd, but this time not to Hubie but to each other and so many friends and relatives. One exception, Hubie's sister Lorene, had written a 4 page letter to Hubie on April 2nd. On the back of the final page after she signed the letter, she added:

"Just as I got the envelope addressed to you last nite, we received a telegram stating you were missing since March 15 in Germany. You know how this makes us feel. We are praying the Lord is keeping you safe somewhere for us. We are anxiously waiting for further notice. We have let Doris know. The Telegram stated they'd let us know more promptly if they heard. It always takes so long though. Praying you are safe, Love Lorene"

Letter from Lorene Kleiboeker to her brother Hubert, 2 April, 1945

"About two weeks ago I dreamed all night about Hubie. He had gotten so tired and fell asleep, and got lost from his company but found them again. And the other night I dreamed we had a letter written March 17th so maybe he has written a letter on that date in a prison camp. Let's hope my dreams come true. They have before..... Always thinking of Hubie and you, if Hubie is a prisoner, we no doubt won't hear anything from him until after they finally quit fighting unless our armies get to the camp before that. We know God is good and pray he will bring our Hubie back."

Letter to Leona Kleiboeker from sister Elda Haunschild, April 9th, 1945

Hubie's parents wrote to the US Army on April 8th and specifically asked if "Hubert's Sergeant (whom he has written about often) might tell us about his missing or when he was last seen". But this letter was not immediately answered. Instead, they got the next Telegram on Tuesday, April 10th, from the same Adjutant General Ulio who sent the first telegram, but this time informing them that Hubie was Killed In Action on March 15, 1945.

April 10, 1945: Kleiboeker Family receives KIA Telegram

While the Kleiboeker Family was trying to absorb the magnitude of the loss of Hubie, which they learned about on Tuesday April 10th, that week in April did not slow down for them. On Thursday April 12th, just two days after they heard of Hubie's death, storm clouds threatened and the sky turned scary. Here is how Alvin, Hubie's older brother told the story: "I had finished sowing oats and noticed a large dark cloud with a strange purple and green cast with lightning in it. The lightning did not go up and down. It was going from side to side in the cloud!" Alvin's wife Alice continued: "He had put our cows into the barn, and came to the house fast, and told me there was a storm coming. I could see how dark it was getting...there was an eerie stillness and then I heard these chunks of ice hitting the roof." It was 7:30 pm in the evening. Alice grabbed her 8 week old daughter Karen, and her two year old David grabbed two caps and his coat and they all went down to the smoke house cellar, where they kept their canned goods. Alvin tried to close the cellar door, but the wind ripped it out of his hands. "The roar was like a freight train" remembered Alice, just as she remembers all her canned fruit and vegetable jars clinking against each other. David who was less than 3 years old at the time can also still remember the fruit jars rattling and seeing chickens come flying in on top of them. Finally it became quiet again. Alvin looked up and could not believe his eyes. The cellar roof was gone, his house was gone. They could see the sky through the big maple tree that had been blown down over the cellar. They had to climb out through the limbs of the tree. Alvin continues: "Then I saw the barn was blown over, the brand new brooder house was gone, everything was blown away. We were soaking wet, but we were alive." Every chicken was killed, the pigs had boards speared through them, they all died. David remembers the refrigerator now sitting on the other side of the road, and when it was opened an unspilled pitcher of milk was inside still full. Some of the cattle were saved through herculean efforts of fellow Freistatt farmers who came to help Alvin chop through debris to rescue 12-13 cows who were in the bottom of a heap of wood shards that used to be the barn. Of course many other neighbors and relatives all had damage from the storm that night, but no one had the damage incurred by Alvin and Alice.

Alvin and Alice moved in with Alvin's parents, August and Hulda for several weeks. Alice was informed yet that week that her younger brother, Verner Nelson, who was one of the local Freistatt boys who went to Camp Hood with Hubie and then to Europe as well, was injured severely with an enemy bullet penetrating both cheeks. More on Verner's story can be found here and here. Verner had to endure many operations and lifelong scars. Then in that same week, one of Alice's other brothers, Frank and his new wife, Elda (nee Lampe) buried their newborn daughter, Elaine Nelson. And finally yet that week, they all found out that President Franklin D Roosevelt had died that same Thursday, the day of the big storm. Hope does spring eternal for those that love God, and these families rekindled their faith and hopes and dreams and carried on.

On April 21st, Hubie's father, August received a letter from the Division Chaplain, L.L. Langford, who stated "As Protestant Chaplain is was my sad duty to officiate at his burial. I wish to assure you that he received a service in keeping with the high principles for which he made the supreme sacrifice. He was laid to rest in a cemetery that is nicely located and the surroundings have been developed as beautifully as possible. His individual grave is cared for with the reverent respect and honor which is due our national heroes." And on July 9, 1945, August finally got a response to his inquiry letter of April 8th which stated: "His (Hubie's) company had captured the town of Utweiler Germany when your son was killed. He was buried in the beautiful US Military Cemetery at St. Avold, France; Plot I, Row 11, Grave 1284."

The family decided to hold a special memorial service for Hubert on Sunday afternoon, April 29, 1945. It was attended by over 600 people. Pastor Stuenkel of the Freistatt Church gave the sermon and it was quite personal as Hubie and Rev. Stuenkel had exchanged quite a few letters and Hubie had stopped in to see the Pastor on his leave in December. The Walther League (Lutheran Youth Group) Choral Union and its male quartet rendered special selections. A specially prepared memorial scroll was given by the church to Hubie's Father, as well as a message from the US Army's Chief of Staff, George C. Marshall and the American Flag. The family gave $100.00 of Hubert's savings to mission endeavors of the church, and relatives and friends contributed almost $500 to a Hubert Kleiboeker Memorial Fund to be used in the building of a new church. The Service closed with the sounding of taps. It was a difficult, emotional day for the family. Tears were shed and hugs liberally exchanged.

Discover Kleiboeker Cousins's Rich History

Hubie's Funeral Service of April 29, 1945. Note the banner on the right with the 53 blue stars. Now there was a bronze star on the table to the left of Hubie's picture but Hubie was still in Europe

Hubert Buried in France -- April 1945

As Chaplain Grapatin was still serving in the 7th Army in Europe, he first heard about Hubie's death in May 1945 in a letter from Pastor Stuenkel of Freistatt. He made some inquiries at the 7th Army's head office at the time in Salzburg, Austria. He found out where Hubie was buried and committed to visiting Hubie's grave, if possible. Finally in July of 1945, after the 7th Army had made its way through the Siegfried line, to Munich and on to Berchtesgarden, where Hitler had his summer alpine personal retreat, the 7th was no longer at war and Chaplain Grapatin was now doing administrative duties near Kassel, Germany. As a result of his change in roles, to administration, Chaplain Grapatin was now able to come home. He described such in his sermon at Hubie's 1948 memorial service: "In August, I received word that I was going back home to the USA. I was assigned to another Division and joined them near Wiesbaden Germany. In early September we started our long journey for home. En route to the port of embarkation, Le Havre, France our long convoy stopped in Metz France overnight. I asked the Colonel's permission to break out of the convoy the next morning to drive to St. Avold which was between twenty and thirty miles away. The permission was gladly given. I arrived at the cemetery, located Hubert's grave, had a short service, took several pictures, and hurried back to the Convoy."

1945 - April to June

St. Avold Cemetery in France as it looked in 1945, arrow indicates Hubie's gravesite where he rested from 1945 to 1948.

Chaplain Grapatin at Hubie's Gravesite in St. Avold France

The US Military Cemetery at St. Avold (as it looks today) now named the Lorraine American Cemetery and Memorial is the largest US Military Graveyard of WW2 Soldiers in Europe. Hubie was buried alongside 16,000 other soldiers. Most of those interred died in the autumn of 1944 and Spring of 1945. This was during the Allied advances from Paris to the Rhine as the Americans sought to expel the Germans from the fortress city of Metz and advance on the Siegfried Line at the German border. Those buried were mostly from the U.S. Third and Seventh Armies.

On June 11, 1945, Hubie was given the Purple Heart and it was sent to August and Hulda Kleiboeker with a certificate signed by Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson. Hubie was also awarded the Combat Infantry Badge.

On August 17th of 1945, Hubie's parents received a letter and box from the "War Department, Army Effects Bureau". The letter stated: "I am inclosing a check for $17.41, representing funds that belonged to him. The remainder of the property is being forwarded to you in one package."

This box was shipped by the US Army Depot to Hubie's father and contained items Hubie had carried with him during the war. It included photos of his friend Doris, his special nephew, David, his parents and his sisters Elda and Leona. It also included his Lutheran Communicant Member's Card, his driver's license, fishing license, Infantry Training Certificate and prayer books and one letter to his parents which he started but never finished.

August and Hulda Kleiboeker Family Portrait taken in 1945.

Back Row from Left: Lorene, Alvin, Meta, Elda, Leona, Martin, Vera.

Front Row from Left: Lorn, Hulda, August, Evelyn

On May 7th, 1945 Germany signed an unconditional surrender of all German forces. This became known as "V-E Day" or Victory in Europe Day. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide on April 30th, and some German Generals continued fighting on various fronts until the surrender. Clearly there was rejoicing here in the US, but in Freistatt, many of the local boys were still fighting the Japanese in Asia. On August 6th, US Forces dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later, they dropped another plutonium bomb on Nagasaki. Some forces continued to fight until September 2nd, when the Japanese Emperor signed an unconditional surrender on board the USS Missouri, in Tokyo Bay. Finally all the Freistatt boys serving in the armed forces could begin their journey home.

The Kleiboekers, like the rest of the country attempted to return to a normal life. Gradually ration cards for key supplies of rubber, oil, and gasoline went away. Food became more plentiful as more and more companies were able to re-engineer their businesses to a normal "non-wartime" economy. The Alvin Kleiboeker family, after the debilitating tornado, had to start over. Kit Worm, the owner of their farm was very frugal and although he rebuilt the destroyed house there, Alvin and Alice referred to it as "the Crackerbox". This new Crackerbox house was not built with a basement to save the Worm's money. Alvin often related that "Momma was having bad dreams and was afraid whenever the sky looked stormy" so Alvin was not going to move his family into a house without a storm shelter! Alvin dug a basement with his own hands creating an entrance right by the back porch and it was ready by their Thanksgiving 1945 move-in date. Alvin continued to work the rented farm and he utilized 2 acres of the Worm farm for growing strawberries. He described strawberry picking as "tedious backbreaking labor in the hot sun" but it paid well and Alvin had reliable pickers (some of which were his direct relatives) and soon he bought his first tractor in those years, a John Deere Model B with steel wheels. Later in 1950, he finally had enough money to stop renting and buy his first and lifelong farmstead near Stotts City where he had to clear the land and build a home to live in. That farm is still owned and occupied by his grandson and family.

1948 -- Hubert is returned to the US and buried in Freistatt, Missouri

Three years had past since Hubie's death in March of 1945. In the Spring of 1948, the US announced the formal program to return World War Two dead from foreign soil. At that time most countries just left their dead where they were, but the US through an Act of Congress ensured families had the option to have their boys returned. The cost of the project was estimated at $500 Million and would last 18 months. There were 454 burial sites around the world in 86 Countries and islands. France alone had 24 US Burial Grounds. The next of kin had 3 choices available: 1) return the body to the US and be buried in a National Cemetery like Arlington, 2) return the body to a private cemetery in the US or 3) remain buried in their current foreign cemetery, if it was designated as permanent, as St. Avold was. But in many countries the cemeteries were only temporary, and the US government declared that all bodies now buried in China, Burma, India, The Malay states and the Dutch East Indies, all islands in the Pacific except Hawaii and many other locations would all be sent home. Liberty and Victory Class Ships designated for this honorary transport of these soldiers were painted white with a purple band around the hull. The caskets were all walnut stained, each covered with an American Flag. Each burial ship carried between 6,500 and 7,000 war dead. All European Theater of War Ships returned to New York ( Brooklyn Harbor) and all Pacific War ships returned to San Francisco. At this time, there were still many who remained "Missing in Action" and about 4000 who were buried in foreign locations with no identification. Keep in mind that over 400,000 in total had died in World War II.

August and Hulda had to wait patiently for a letter from the US Army on whether or not Hubie might be sent home. They saw many articles in the newspapers announcing this major relocation of boys who had died outside of the US. They cut out every article they saw and added it to Hubie's scrapbook. 20,000 families across the USA were waiting for their letter. Finally August and Hulda received their letter in the summer of 1948 and they requested that Hubie be sent home to be buried at their local Freistatt Church. Many relatives of others who were buried at St. Avold made the same decision to send their boy home. But even so, today 10,489 Soldiers remained buried at St. Avold of the 16,000 originally there at the end of WW2 in 1945.

On these Liberty and Victory Ships, the military regarded service personnel remains not as cargo, but as passengers whose names appeared on a “Passenger List, Deceased” aboard all Army Transportation Corps ships that brought the dead from overseas. That status also applied aboard mortuary rail cars that transported the soldiers from the US harbor to their final destination. The Army paid railroads a special reduced fare for each repatriated casualty and, for guards and military escorts, as with any troop movement, the regular fare. Congress gave the Army until December 31, 1951, to finish repatriation, including search, recovery, identification, transport, and burial. Beginning in 1947, the Army Transportation Corps took delivery of 118 specially modified mortuary rail cars. These all had originated as wartime hospital cars—standard heavyweight parlor, lounge, and observation cars, plus a few sleeping cars and one railroad business car, that had been converted into hospital ward, ward-dressing, and unit cars between 1941 and 1943. Workers gutted each interior, removed unneeded underbody equipment, and installed three-level roller-equipped storage racks to accommodate containers holding remains. As mortuary trains left the station, Army Depot Centers were receiving messages from port personnel on the number of remains being shipped, the railroad and train numbers, military identification number, date and hour of shipment, and estimated time of arrival.

This information was then distributed widely to national and local media about who was on each ship and railroad car. The Newspaper article shown here (one of many collected by the Kleiboeker Family on this shipment issue) states that Hubert was "returned to the US from Europe on the US Army Transport Carroll Victory (Ship)" and expected in about 2 weeks. Another Nov. 15, 1948 article stated that "the Carroll Victory ship carrying the bodies of 7,600 Americans killed in Europe in World War II docked tonight at the Brooklyn Army Base. The Army said this was the sixteenth and largest shipment of war dead to be returned from any theater of operations....Memorial Services for the returning dead are to be held tomorrow at the (Brooklyn) army base."

It was appropriate for Hubert to come home on that Carroll Ship. Prior to being commissioned as a war dead transport ship, from 1945 to 1947 the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and the Brethren Service Committee of the Church of the Brethren sent livestock to war-torn countries. These "seagoing cowboys" made about 360 trips on 73 different ships. The Heifers for Relief project was started by the Church of the Brethren in 1942; in 1953 this became Heifer International. The SS Carroll Victory was one of these ships, known as cowboy ships, as she moved livestock across the Atlantic Ocean. Carroll Victory moved horses, heifers, and mules as well as chickens, rabbits, and goats. As a family of farmers, Hubert's family would have been proud that this ship had been used to help other farmers and their livestock before bringing Hubie home.

August and Hulda received their final telegrams from the US Army in November 1948. The first to confirm Funeral home arrangements and delivery, and the second which is shown here, announced Hubie's arrival at the Monett Train Station on Frisco Train Number Three at 6:25 am Monday morning on November 29th, 1948.

Military Escorts accompanied every casket sent home. These escorts had a special role as the only government representatives to have face-to-face contact with next of kin. Each was picked from a pool of volunteers, many of them combat veterans asked to reenlist specifically for this mission to assure that someone of the same service branch, race, sex, and equal or higher rank accompanied each deceased soldier. Escorts underwent five weeks of training, including advice from psychiatrists on what to expect and how to respond to reactions and questions. While traveling with remains, escorts were assigned coach or sleeper space, depending on a trip’s duration, and were forbidden to consume alcohol. The escort also carried a new flag for the funeral, blank rounds for the graveside firing party, and reimbursement forms for the family and funeral director. These reimbursement forms signed by August Kleiboeker still remain in the Hubie Scrapbook. The Army initially feared that escorts’ presence would disturb families, but these personnel were universally found to be one of the program’s greatest assets.

On Monday morning, Nov 29th, 1948 at 6:30am, Frisco Train Three rolled into Monett Station. Waiting there on the platform were 22 members of the local Freistatt American Legion Post which was founded in 1946 and named after Hubert H. Kleiboeker, as it remains today. Many of these 22 were part of the original 10 from Freistatt that Hubie trained with prior to leaving for Europe, as seen in the article shown. Also on the train platform were a delegation of Monett area War Dads, all who had lost sons in the war.

Hubie was transported to the Bennett and Wormington Funeral Home in Monett that Monday. On Tuesday, he was then laid in state back at his home on the farm until the final Memorial Service on Sunday December 5th at 2:00 pm. Those six days, August and Hulda's home was the visitation place for all the relatives and close friends. The Military Escort was there each of those six days and participated in the funeral on Sunday.

Hubie leaving his home for the last time

Floral Bouquets were abundant that day, here being carried by Hubie's nieces and nephew.

Hubie arriving Trinity Lutheran

Rev. Stelling (left) and Chaplain Grapatin(right) arriving Trinity Lutheran Church for Funeral

Floral Tributes before going into Church

Firing squad led by Martin Osterloh, a WW1 vet, with Frank Nelson, Vernon Koenneman, Melbert Moennig, Cecil Doss, Elfred Knaust, Virgil Mattlage, Edward Worm

Both Reverend J. W. Stelling and Chaplain Grapatin officiated at the impressive military tribute for Hubert. (Chaplain Grapatin, still in the US Army was now stationed at Camp Chaffee, near Fort Smith Arkansas, which in 1941 -1946 was also a German Prisoner of War Camp.) The Service for Hubie included the quartet of Frank Nelson, Verner Nelson, Alvin Fritz and Raymond Fellwock who sang "Jesus Lead Thou On". They were accompanied on the organ by Prof. Paul Rottmann. As can be seen in the photos above there were many floral bouquets which were carried in by Hubie's various younger relatives: Aletha Faye Kleiboeker, Arlene Kleiboeker, Clara Kleiboeker, Mildred Mattlage, Ardice Hesemann, Marion Rusch, Patty Rusch, Marilyn Kleiboeker, Carolyn Kleiboeker and of course his favorite nephew, David Kleiboeker. Pallbearers were all members of the Hubert H. Kleiboeker Legion Post No. 419: Vernon Kleiboeker, Melbert Holle, Martin Holle, Martin Schoen, Verner Nelson, and Norman Lampe. Honorary Pallbearers were Raymond Bracht, Walter Holle, Chesteen Fleming, Norbert Obermann, Eddie Joeckel, and Ervin Hesemann. The Color Guard and Color bearers were Elmer Kaiser, Erwin Krueger, Junior Karr, Maurice Ray and Marvin Holle. Buglers were Homer Lee and Homer Oexmann.

Chaplain Grapatin delivered the sermon that day which was quite personal and told the story of his meeting Hubie back in March of 1945 at the Nancy Rest Camp. The Chaplain centered his remarks around the text of Romans 8:28. "We know that all things work together for good to them that love God." It was a loving and very personal tribute to Hubie. Chaplain Grapatin concluded his remarks with a quote from a woman he met in Alsace France. "Herr Pfaarer, Sie haben alles weg genomen, aber nicht den lieben Gott!" Here was a french woman who spoke German that almost all the participants at Hubie's funeral could understand: "Dear Pastor, The enemy has taken away everything, but not our dear God!" Grapatin continued: "She lost her home, her cows, chickens, yes everything she had, but not God. She still had God. And so no matter what may happen to us, may we never lose faith in God." A copy of Reverend Grapatin's sermon is available for further reading here.

Hubie's parents, August and Hulda, his six sisters and three brothers, and especially his brother Alvin had all lost a great deal these past few years. This service was hard to experience but the family knew that all things work together for good. His parents and siblings all had strong faith and that faith remained a guiding foundation throughout each of their lives.

Hubert's Grave in Dec. 1948. Note shocks of Corn in background standing in the field.

A memorial fund was set up in Hubert's name to be used in the building of a new church. Over $500 was contributed from his first memorial service in 1945, and more was given from the funeral service in December of 1948. A new and much bigger Freistatt Church was built and consecrated in January of 1955. The sign above commemorating Hubert is now a permanent part of that new church building.

Hubert's Grave with Army issued Tombstone in the 1950s

Original Army Issued Grave stone. This was in place until the 1980s, when it was replaced with a newer more permanent headstone.

Hubert Kleiiboeker's present day headstone in the Trinity Lutheran Cemetery, Freistatt, MO.

We are indebted to all young US soldiers, not only in WW2. For us, who are part of the greater Kleiboeker Family we especially remember and thank and honor our dear Hubert. Kleiboekers began arriving in the US from Germany as far back as 1834. Hubert was the first descendant of any Kleiboeker to return to Germany. But he was there less than a day. He was killed within 320 miles (510 km) of the original Kleiboeker farmstead where his ancestors had lived.

Hubert was full of life and energy and blessed with a generous heart. From his many letters, it was clear that he cared about his family, the farm, his local church and community and was steadfast in his faith. We can be proud to have had such a patriotic relative who gave his all for all of us.

Dennis R. Kruse

Nephew of Uncle Hubert

Originally written August 30, 2010, updated August 2020 with special thanks to Aletha Kleiboeker Schoen, David Kleiboeker, Orville Osterloh, June Kleiboeker Huff, Anita Kleiboeker Breazeale, Karen Kleiboeker, and Jane Schnelle Mayden for their stories remembered, artifacts collected and overall help with this document. Special thanks to all of Hubert's siblings, now no longer with us, who collected and saved all his letters, newspaper articles, pictures, telegrams and things that were special to Hubert H Kleiboeker.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.